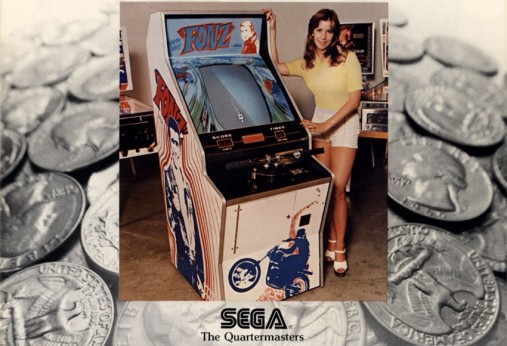

Ayyyyyyyy! Sega brought The Fonz to arcades in 1976

I don’t feel that enough video game writers have a real grasp on the history of the industry, and it shows. Just recently, I read one of them rant about how the industry licenses other entertainment properties a lot of the time now, raving about games from Game of Thrones to Family Guy to South Park to Spider-Man all over E3.

Making video games out of other entertainment properties is not exactly a new thing, just as most complaints about the modern day video game industry involve aspects that have always existed. The 8-bit and 16-bit eras were full of enough generic side-scrolling shovelware based on films and TV shows to fill 20 columns, and I almost thought about going back a bit further and pointing out the Atari E.T. debacle or the fact that the band Journey had numerous games as well.

Instead, I’m going back even further than that, all the way back to 1976. Happy Days was the hottest show on television, and a video game name that nobody knew much about just yet brought the star of the show to arcades across the country.

Sega’s Fonz video game was a repackaging of a previous title also released by Sega in 1975 called Moto-Cross. With Sega’s US branch then owned by Gulf & Western, the company with access to the rights for Happy Days, this was perhaps the earliest example of a popular entertainment property being used to help sell a video game product.

The object of the game was to help the Fonz race against the clock and stay on the road as he weaved and “aaaayed” between opposing motorcycles. Some of the technology of the game, including sprites changing size depending on how close or far away they were from the camera and handlebars that gave motion feedback upon a collision, joined with Henry Winkler himself on the cabinet artwork.

Despite the pop culture tie-in, Fonz is often forgotten by even the most detailed of video game vets, lost in that historical void that seems to exist between Pong and Space Invaders. Nonetheless, it is a suitable example to bring up to any modern-day critics who fail to realize the video game industry has almost always based product on other forms of entertainment media and always will.