Kineticism and Violence in Games

No player can deny that over its history, violence (both realistic and cartoonish) has permeated the video game industry. From the innocent jumps of Mario onto a nearby Goomba, to the brutality of Manhunt, violence has become an almost inescapable part of video game design and culture. Some parents, teachers, politicians and a certain disbarred Florida attorney might say that these games are popular because of their base, gruesome gameplay and that the average gamer is infatuated with violence and gore, essentially turning him into a volatile sociopath bent on murdering innocent people. While I’m personally not even against the theory that violence in games is desensitizing players (it seems possible to me), I think that the murder-training label for games is a bit much. As well, I think I have a bit of an idea as to why video game violence is attractive to gamers.

Last year I was pointed in the direction of an interview Pitchfork conducted with founder of Ska Studios, James Silva (creator of gems such as I MAED A GAM3 W1TH Z0MBIES 1N IT!!! and The Dishwasher: Dead Samurai). The beginning of the interview somehow quickly stumbled into the subject of video game violence (not surprising since Silva’s games have been known to include their fair share of blood), and it was then that James Silva solidly grasped a concept I had been trying to work my mind around for years.

“For me, a movie that is about torture, like Saw movies—those make me squeamish. When it’s all about the pain and the suffering—that makes me squeamish. Seeing surgery on TV makes me squeamish. Getting blood drawn makes me pass out. But in a videogame, where it’s about chopping off limbs, especially the way it’s presented in my games, it’s more like taking a hammer and smashing a TV in real life. You love seeing glass explode everywhere, and carnage and debris. It’s all about the kinetic action where everything explodes, and it’s so visceral and satisfying.” – James Silva

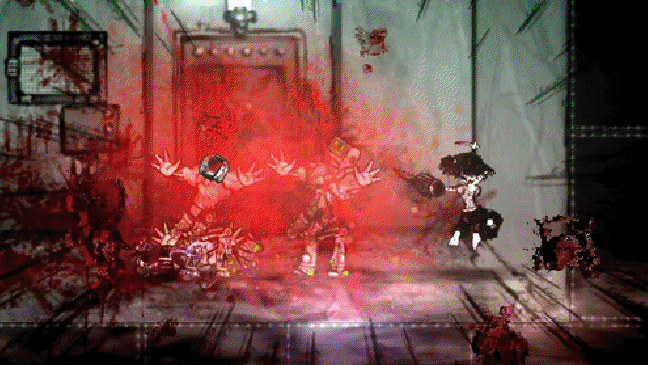

Gamers like violence, not for the violence itself, but for the kinetic way in which it’s presented. It’s not about using a sword to slash an enemy, it’s about the unrealistic blood fountains and flying limbs that accompany that slash.

In Silva’s one quick answer, everything suddenly clicked for me. Now though, I will take it a step further by explaining not only how it applies to the games made by Ska Studios, but to all games, and why the games that focus on realistic, brutal violence often fall farther from the mark.

The idea of kinetic hits has been around as a way to entertain gamers since the early days. Take, for example, Link to the Past. In The Legend of Zelda: Link to the Past, a successful hit on an enemy with your sword will often cause them to be knocked back, flying several feet away, and upon killing them, they poof or pop. In real life, when you slash somebody with a sword, they just fall over and lie there ’til they die. Now imagine how boring Legend of Zelda would be if you hit an enemy and they just rolled over. It wouldn’t be near as exciting, because the violence would be too realistic and stationary, and that isn’t what entices gamers about the violence.

This purposeful lack of realism in its violence can be observed in almost any game on the market. What would No More Heroes be without its stylistic explosions of blood? Would fighting games be near as interesting if you couldn’t hit an enemy thirty times while airborne and then smash them into the ground only to have them stand up again? No, if fighting games went like real fights, where two guys stood face to face and took swings in pretty much the same standing position until one passed out, it would make for boring gameplay and visuals. It’s much more catching to the eye and to the hand if a player, instead of just punching someone, can punt their body forty feet in the air and have them come back down, shattering concrete.

Any child trying to replicate this will have a few major problem. One being that no real violence looks like this, the other being that most kids don’t have a light-saber.

The idea of a fast, exciting, and visually entertaining design can also be useful in relaying information to the player. In Call of Duty, when a player is damaged, blood splatters quickly on the screen, partially obscuring the player’s view for a moment before fading away. This is a prime example of exciting violent kineticism even to the victim player. If in Call of Duty, the player took fall damage and, instead of seeing a quick splatter of blood that appears suddenly on the screen, the screen got a tiny splotch of red, that then slowly grew larger as you tried your best to keep battling on your now-broken legs that are constantly bleeding out, with a final crescendo of red totally obscuring your view before finally dying and respawning, a large amount of players would find it terribly irritating and possibly even sickening or disturbing.

Now, there are those exceptions that use the lack of kineticism to their advantage. Manhunt, for example, is known for its gruesome and realistic portrayal of killing. The game’s detailed and realistic violence (only hindered by the day’s technology) serves to disturb the player and leave them more grimly curious than fun and excited. Such an approach can be taken with games, but is less common because the realistic lack of kineticism serves only to make it less fun and more gruesomely enthralling. Or, as the Chicago Tribune said:

“… Manhunt also is the Clockwork Orange of video games, holding your eyes open so as to not miss a single splatter — asking you, is this really what you enjoy watching?”

Any parent who allows their child to play a game like this has someone else to blame besides the game industry.

And generally, the answer is no. Most gamers recoil at the savagery of games like Manhunt. They want quick and visceral violence like that of God of War or No More Heroes. Gamers don’t want violence for the pain of the victim, but for the eye catching way the violence is presented. This explains why games that have kinetic visuals that aren’t even violent (like Wave Race 64) sometimes become as popular as their violent counterparts.

Violence exists in games the same reason explosions permeate action movies (which hilariously enough have also been attacked for poisoning the minds of the youth): it is visually eye catching and unrealistic. Violence in video games is not there to feed some demented blood lust. Likewise, it does not brainwash us into gore-mongering killers.

To close, in the words of fellow gamer Asai Nero Tran: “Show gamers a real man dying and their responses will be the same as any non-gamer’s response: they would be horrified.”

—

Daniel Lamplugh, or as he is better known in some circles, Gaarathedancingpanda, is a passionate game enthusiast who has not yet escaped his teenage years. Armed with the mentality of an eight year old, and a slightly above average vocabulary, he travels the net trying to explain the virtues of video games to fellow internet people. He can be followed on twitter @thedancinpanda.

—

Sources for quotes:

James Silva will destroy anyone who gets in his way

[http://pitchfork.com/killscreen/113-james-silva-i-will-destroy-anyone-who-gets-in-my-way/]

`Manhunt’ a solid game, but do you want the gore? [http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2003-11-24/

features/0311240161_1_manhunt-video-games-violent-game]

Violence in Video Games [http://asainerotran.tumblr.com/post/40300851870/violence-in-video-games]

More on the Subject:

Jimquisition: Desensitized to Violence [http://www.destructoid.com/jimquisition-desensitized-to-

violence-241921.phtml]