Insert Currency

Insert Currency: Assassin’s Creed – A Persian History

Ubisoft, and other modern gaming behemoths, no longer conjure new concepts from the ether. Ideas don’t come into this world screaming, wailing, and covered in placenta. Instead, like so many Pokemon, they evolve. Your Prince of Persia is now an Assassin’s Creed! Each new franchise goes through a multi-year period of development and refinement, as did Assassin’s Creed and its gargantuan 15 iteration span of sequels and novels, but the genesis of the core game dates as far back as 1989’s Prince of Persia and 1987’s Metal Gear.

When talking about platformer genesis, then 1981’s Donkey Kong and Jumpman are the Adam and Eve of the genre. The agility of Assassin’s Creed’s Altair with which he scales towers is, in effect, little different from an early Jumpman’s 2-D ascent towards the notorious, crying for help with anger management, Kong.

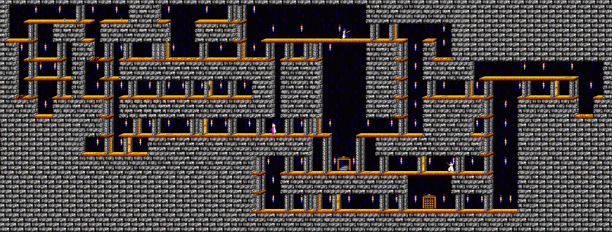

Despite Donkey Kong being owed an enormous, Greek-sized, debt by all platformers, it is the 1989 Apple II hit Prince of Persia from which Assassin’s Creed traces a more pure lineage. Prior to Prince of Persia the genre was dominated by linear side-scrollers. The orthodoxy of the time was to accept games as artificial and focus primarily on designing sequential challenges for the player to overcome. Embodying a charmingly upbeat philosophy of “only looking forward,” after advancing past a specific obstacle it was typical that there would be no reason to go backwards, and in fact, games often did not allow returning at all. While this strategy yielded a great number of classics, Prince of Persia’s vision diverged from the norm. It focused on the gameplay-feel instead of the obstacles. This resulted in two notable hallmarks, rotoscoped graphics that imitate life-like animations, and sprawling, open, dungeons.

Prince of Persia designer, Jordan Mechner, traced images of his brother running and jumping in order to have player movement that was natural. Mechner, however, remains tight-lipped as to the source of the animation triggered when the player falls to his death. This was in stark contrast to the most notable platform franchise of the time, Mario, wherein the protagonist defies physics by being able to jump several times his own height and uses his head like a rocket-powered sledgehammer. The decision to use the process of rotoscopy involved an important imagining of where the medium should go. Many games are quite happy to be fantastic and unconstrained by the moors of physics and other generally limiting natural phenomena. Prince of Persia instead strives to be life-like and it is that same impulse that shaped Assassin’s Creed. Assassin’s Creed takes this so far as to model its geography and setting on real locations. If you think about this for a moment, it’s actually thrilling. Modeling navigable real environments is something you might expect the department of education to fund if it had a budget that was big enough to at least cover art supplies. Instead you have a franchise that is increasingly an amalgamation of history lesson and fantasy. The Ubisoft franchise is at the vanguard of a movement to make games that model reality, but more exciting.

The introduction of complex multi-story levels that inspired later hits such as Duke Nukem, the Oddworld Series and Assassin’s Creed’s did more than just make the L button on a d-pad relevant, it opened up the possibility of having players get lost, or to innovate unforeseen answers to puzzles. Re-traceable dungeons were important because they kept the player critically engaged. Facing an immediate threat, such as a barrel in Donkey Kong, is radically different from being placed in an open environment and let loose. Prince of Persia’s adoption of this ideal, as a level being an entire area instead of just everything on the screens to the right, is one that Assassin’s Creed upheld unwaveringly. Design based on freedom of movement created a great sense of control that would have long-lasting appeal.

The introduction of complex multi-story levels that inspired later hits such as Duke Nukem, the Oddworld Series and Assassin’s Creed’s did more than just make the L button on a d-pad relevant, it opened up the possibility of having players get lost, or to innovate unforeseen answers to puzzles. Re-traceable dungeons were important because they kept the player critically engaged. Facing an immediate threat, such as a barrel in Donkey Kong, is radically different from being placed in an open environment and let loose. Prince of Persia’s adoption of this ideal, as a level being an entire area instead of just everything on the screens to the right, is one that Assassin’s Creed upheld unwaveringly. Design based on freedom of movement created a great sense of control that would have long-lasting appeal.

The twin hallmark challenges of a platformer, timing and hand-eye coordination, are fundamentally untouched, but the scenery and scale have blossomed beyond what would have been conceivable in 1989. The expansion of playable territory has remained an obsession within the gaming industry even today. Although Assassin’s Creed is related closely enough to Prince of Persia to prevent a legal marriage, it is no way a clone, and that is because it takes, in equal measure, from stealth-based games such as Metal Gear Solid and Thief. In the next part I will talk about how these games have also influenced Assassin’s Creed.